|

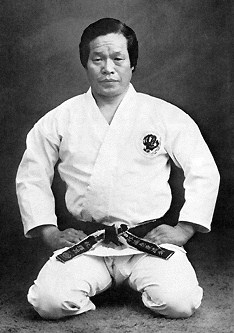

There’s a photo of our system’s founder, Teruo Hayashi, on the wall of each WKA school and likely placed similarly to the front of every Hayashi-Ha Shito-Ryu dojo across the world. In our opening ceremony, typical to traditional Japanese karate systems, we take time to acknowledge the concentration and deference required of serious training. We line up in a hierarchical manner with the senior ranking student leading the class, instructing the student body to face the sempai or Sensei facing the group. After requesting ‘Sensei (Shihan, Hanshi) please train us’ in Japanese, the assemblage turns toward a picture on the wall and bows saying in Japanese ‘To Soke, bow’. I’ll pause here because I recall wondering about a.) the bow b.) who was the man on the wall to whom we deferred?

The entire opening ceremony answers this question, in my mind. It is a reminder of a legacy of instruction, coming our way, a result of someone’s else’s diligence, patience, and generosity. That photo on the wall reminds us that we are the beneficiaries of exponential knowledge because a rare person took the time to learn, distill, refine and canonize vast information. The more we learn—in any forum—the more we respect those responsible, motivated, vested researchers and practitioners that preceded us. Theirs was a gift of valuable information gleaned from great effort and dedication. As a parent or friend, we can learn these same lessons of the sacrifices required of those who generously share their ideas of cultivation, compassion, and passions. Such mindful gifts are rare but they spread across any culture, every civilization. We want to make the best of ourselves with humility in mind. Such recognitions are prompts. It’s important for us to be mindful of those who share knowledge. Soke’s photo reminds me now of our many interactions, talks, slaps on my legs and body to ensure perfect execution. It reminds me of Hanshi Thiry’s sacrifices, too. I certainly am reminded that I would not have likely undergone such trials; it makes me grateful. The ceremony, therefore, has more meaning for me now 37 years later. As a beginner, I simply recognized it as a very nice protocol and nothing more. The bow, however, grows to means something. And, it’s a reminder not unique to Karate. When we defer to grandparents who in the elder years have waned but stand tall for their selfless contributions to our lives, we are also, in a sense, bowing to tradition. We open the door for them, allow them to eat first, pander to them proactively. Our parents deserve the same courtesies as they struggle to inculcate and pass along the best of their experiences and resources, too. The highest ranking Senseis are the most mindful of the smallest details. They think about what they bring to the table, not what they take. Theirs is a position of responsibility, not of ‘power’. Which brings us to the bow to others in the context of Karate. We study Japanese karate and the technical language is Japanese. French is the technical language of Ballet. German and Latin will be the foundations of medical terminology. Beyond the language and culture, it is a martial art. We use common martial art protocols of the Japanese culture—and ours as well-- when we immediately and efficiently respond to instruction, keep our environment clean, speak strongly and articulately, with respect to our instructor, our colleagues, and others. In the American military, the same sort of martial rules applies to those upon whom our lives may rely. Yet, the bow in certain cultural parlances may incorrectly denote religious type reverence rather than deference. A martial art bow —in the context of Karate training-- is a demonstration of humility and deference…no one should represent themselves as anything but a leader of information and responsibility. Reverence, to my way of thinking, makes an instructor the sole gatekeeper of information in a way that is less a matter of advocacy and more of some sort of divine intervention. We humbly acknowledge and trust our leadership. Please do not mistake this respect for worship. When lines like this are crossed, it is cause for concern no matter what circle in which one operates. An instructor with an overinflated ego or an inability to listen, observe or teach/guide objectively, is not a decent instructor. Reminder: a bow is with a straight back, head in alignment with the spine, the eyes of a Karate-ka is not closed but lowered with the head as to maintain a scrutiny of surroundings. This is martial arts: never put yourself in the position of lowering one’s sense of safety. The social bow, however, in Japanese culture (or others) may affect social class and/or submission. A head may be cowed, for example, exposing the neck to the discretion of a ‘superior’s’ sword. Even as the lines of ascension (rank) in karate reflect seniority, it is meant to call attention to a sempai’s knowledge, leadership, respect for others, and sense of responsibility. In lieu of those characteristics, no matter what color belt one is wearing, we may bow as a protocol but elect not to seek or follow their advisements. Ranking of belts is a means of gauging progress to a sensei; it is a reminder of pedagogical advancement to which the practitioner is responsible. We constrain our egos in Karate-do even as we build and temper our abilities to move instantaneously to confront and defend—as if our lives depended on it. It takes a lifetime to harness the impulses to seek or exploit notoriety, as it were. Humility does not mean letting go of our mindfulness in all matters. Whether in a karate dojo, at school, at work, a good karate-ka stays wary of senseless directives and personalities that run contrary to one’s principles or best instincts. Opening ceremony speaks to this in volumes. You acknowledge the forum and demonstrate respect for the opportunities. But, never lower your eyes or head. Never lower your guard. Don’t ignore your moral principles. Pay attention, think about it, be polite but keep your mind alert to irregularities. A student is not the sole beneficiary of a Karate lesson or class. Each ceremony, the Sensei returns a bow in kind. We learn something new each time we teach. Teaching conscientiously allows us to refine our work, improve upon our definitions and reflect upon how we can improve instruction. When we join in cleaning the floor, or conducting exercises, bowing mutually, we remind ourselves of our roles as advocates. We should never forget thanking those—at every opportunity—for the lessons that act as vital character building foundations. Meet and greet politely. Remember to assist a struggling white belt, tie the wayward child’s belt, quietly and without recognition. Open doors, help others proactively and without expectations, approach difficulties in life as challenges from which you will grow. This is all a part of Karate-do. Shihan Thiry Bellevue Dojo |